A coding course or calligraphy – dissertation delved into the right of the poorto develop themselves

According to the Constitution of Finland, the public authorities must ensure that everyone has the opportunity to “develop themselves and indigence must not prevent that.” It is a fundamental cultural right just as free basic education.

The ways in which this fundamental right is implemented are left open and must be assessed in conjunction with the level of social development. In general, the implementation methods have meant leisure activities in education, hobbies and training. Libraries, public swimming pools, adult education institutes, and so forth.

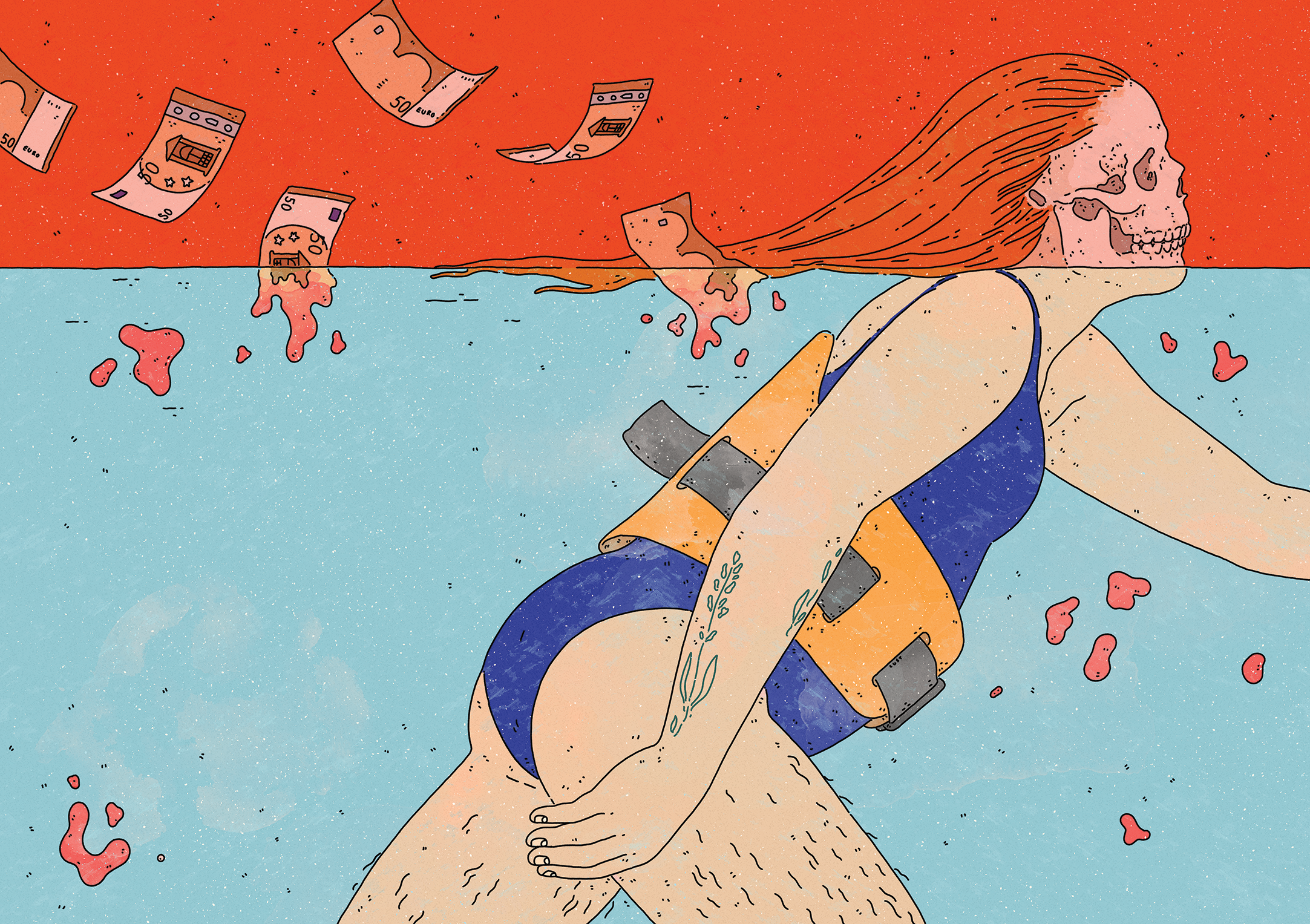

Public Law Researcher Iina Järvinen’s dissertation Itsensä kehittäminen köyhyydessä (Self-Improvement in Poverty) was examined at the Faculty of Management and Economics at the Tampere University in September. In the dissertation, Järvinen asks how well the fundamental right to self-improvement is realised when it comes to those who are poor.

There are a lot of problems indeed. Lack of money still poses obstacles to self- improvement in Finland, Järvinen’s study states. Meaningful leisure or educational activities are not possible for everyone.

We should pay attention to this social problem.

“There has been a lot of talk lately about poverty, because the problems of inequality in society have only expanded and gone deeper. So this dissertation came at the right time, if you can even say that,” Järvinen says.

The topic of the dissertation is also relevant because the government of Petteri Orpo (Kokoomus) is planning cuts of more than 22 million from liberal adult education institutions. These include, for example, adult education institutes and summer universities.

Meaningful leisure or educational activities are not possible for everyone.

The current situation did not come out of nowhere

In her research, Järvinen illustrates the history of Finnish poverty and education work from a class-society to the post-war welfare state and neoliberal austerity policy. In addition to previous research literature, Järvinen familiarised herself with material preparing legislation, such as statements produced by various committees.

According to Järvinen, the current situation has not appeared out of nowhere, but discussions on the very same rights of the poor have been taking place century after century. The long timeline helps put things in context and make comparisons.

Historically, the forms of self-improvement secured by the state first attached themselves to the status and socio-economic status of the individual. Different social classes were considered to have their own cultural needs, which the public authorities should in some way satisfy.

It was only with the advent of the modern welfare state policy that systematic work to achieve equality began. The cultivation of social justice was defined as a fundamental value of the welfare state. Throughout the 20th century, this ethos extended into supporting civilisation with public money.

The mention of self-improvement in the Constitution was recorded with the 1995 fundamental rights reform.

We have not really tried to eradicate the root cause itself, i.e., poverty, from our society. “The aim is to seemingly help the poor and, in actuality, manage them to a sufficient extent so that there is no need to make more permanent decisions,” Järvinen says in her dissertation.

The right to self-improvement is valuable in itself, Järvinen points out. It is also not a question of duty, but of self-determined freedom to choose.

“Self-improvement has been and still is seen as an activity that promotes employment and serves working life. On the other hand, work-related values are visible in earnings-related social security,” Järvinen states.

According to Järvinen, we should be able to approach this right without the weight of the instrumental value associated with employment or the promotion of central government finances. So, a calligraphy course is just as valuable a way for the poor to educate themselves as learning coding that offers new career opportunities.

“Legally speaking, there should be no cuts made for those who are already disadvantaged and vulnerable.”

Doctoral researcher in public law Iina Järvinen

According to Järvinen, education always involves the exercise of power, which means that there are certain purposes and values behind it. What opportunities for activities are offered to those of limited means is a political issue.

“It very much depends on the municipality in question. In terms of entrance fees, for example, there is no provision that poor people should have access to a swimming pool at a certain price, or that they should be able to visit an art museum free of charge,” Järvinen says.

Despite student, pensioner and unemployment discounts, many hobbies are simply too expensive for the poor. Should the opportunity to golf, for example, be secured for the poor?

“I think that those in the private sector who offer these services that promote education or self-improvement would also do well to promote equality,” Järvinen says.

In practice, the government’s planned cuts to liberal adult education would mean an end to many educational institutions that are already under-funded. In August, labour market and education organisations called on the government to back down on the cuts they consider to be harmful.

“Financial cuts would endanger the equal opportunities of Finns for continuous learning. Studying for working-age people would become more difficult in many municipalities. Municipalities’ opportunities to promote the well-being and competence of local residents would be made more difficult,” says the statement of the organisations.

Doctoral researcher Iina Järvinen says that she finds the cuts proposed in the Government Programme worrying in terms of the realisation of cultural rights. Cuts to social benefits, in particular, seem to her to be fundamentally dubious.

“Legally speaking, there should be no cuts made for those who are already disadvantaged and vulnerable. Cutting benefits from people who find it difficult to cope with the ordinary cost of living inevitably reduces the chances of self-improvement as well.”

Järvinen hopes that her research will bring visibility to the fact that the right to self-improvement is indeed laid down in the Constitution of Finland. Civil rights belong to everyone and we should not compromise on these rights.

“Everything is ultimately linked to a dignified, good life, which means more than making sure everyone has just the basic living conditions such as housing, food and medicines,” Järvinen says.